Only the State Journal reported on this special meeting of the Dane County Board where they heard the results of the mental health study. Here’s the rest of the details of that meeting including recommendations and exploring what those recommendations mean for Dane County.

You can follow along here if you feel so inclined. I also blogged about this about a month ago when the study first became available. Abby Becker from the Cap Times also wrote about it in early November.

GETTING STARTED

Absent: Heidi Wegleitner, Tanya Buckingham, Carl Chenowith, Kelly Danner, Patrick Downing, Nikki Jones, Jamie Kuhn, Jeremy Levin, bob Salov, Andrew Schauer, Julie Schwellenbach, Matt Veldran all absent at the beginning of the meeting. (Wegleitner is present by the end of the roll call)

Chair Sharon Corrigan says they will hear from the Public Consulting Group on the Dane County Behavioral Health Needs assessment. They have it on their desks and received the link to it before. They will hear a presentation and then have 30 minutes for questions at the end.

PRESENTATION

Rich Albertoni is there with Kacie Schlegel and Alecia Holmes (I found a bunch of white men on their website, but not these two women).

Albertoni says the project scope was to look at the efficacy of the mental health system in Dane County, the service array, the quality of the system, a focus on the intersection between mental health and criminal justice and then looking at a crisis restoration center.

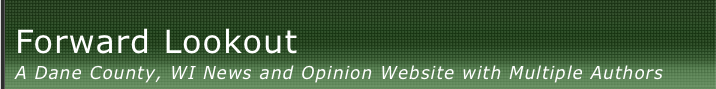

He says that they had two tracks of information they collected: qualitative and quantitative. The qualitative came to them as data collected through the Department of Human Services, its the service data for the services they pay for. They also went to Wisconsin Health Information Organisation (WHIO) for Medicaid, Medicare and Private Pay Data. WHIO is the gold standard in WI for claims data, that lets you do science research. With private pay data, this is a challenge everywhere in the country. That is because employers self fund their own insurance, they may not contribute to a claims database, the disbursement of people who work there are different, he works in Dane County, he is employed by a company in Boston and his insurance is through a company in Massachusetts. That is an example of how hard it is to get private pay info. The info in WHIO is about 42% of the private pay data in Dane County, that is the biggest source of information available.

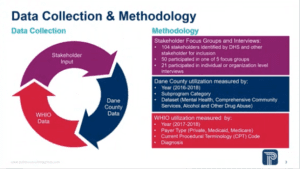

Dane County compared to a lot of counties they have worked with has a much lower uninsured rate and higher private pay. A little bit lower Medicaid rate than you see in the rest of the state where it is 15-18%.

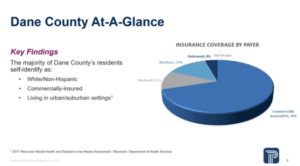

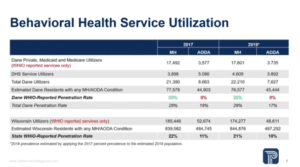

This slide shows the prevalence of behavioral health conditions in the county. This is information from the Department of Health Services. 18.2% of adults in Dane County have experienced a mental illness, 8% of children with serious emotional disturbances and 9.5% for substance dependence. The national data shows that the occurrence is higher in the Medicaid population and the uninsured population.

For the total number of people in the county for the two years they looked at (2017 and 2018) who have a mental health condition (77,000 in 2017) or substance dependance (44,000 in 2017) and they look at different sources of information. 23% used mental health services according to WHIO data, that a little better than 22% statewide. It’s 8% for substance abuse, statewide the number is 11%.

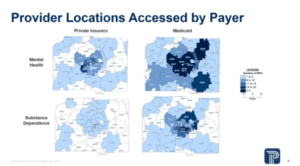

This is the payer source information for people who used services. There is a higher density of users on the medicaid side (shown in darker blue.

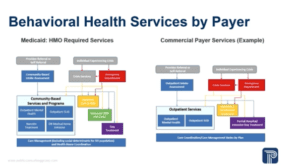

Alecia Holmes says that they spend quite a bit of time looking at service definitions and coding used by different payers to make sure they were comparing apples to apples in the services. She says they looked at how often people were accessing lower acuity services like counselling, things that help keep people in recovery, as well as intermediate levels of care – crisis services and lastly in-patient services. They looked at DHS contracted services based on services from the county. There wasn’t a a lot of difference.

On the commercial payer side they say partial hospitalisation and intensive day treatment, they are higher acuity but still out-patient services. For commercial payers they are often subject to prior authorisation requirements and there is more scrutiny on who would be admitted to those services. The emergency department is still listed as well because they see crises in mental health coming through the emergency department. That is happening overnight when other services may or may not be available.

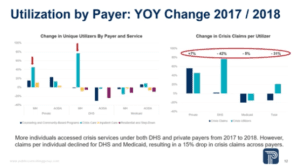

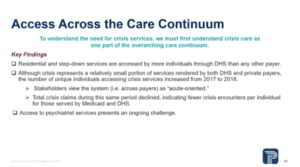

Once they organised by levels of care, they then cut the data to see what stood out. One immediate thing that stood out was that there was a significant increase in the number of different people accessing crisis care in the county and private pay data from 2017 to 2018. They compared that to the claims, while they found more different people accessing crisis services, the number of claims actually went down. Even tho there were more people coming into the system they were returning less frequently. They saw a decline in crisis claims even tho there were more new faces.

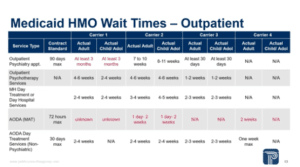

One reason they might see an increase in crisis services is lack of engagement in outpatient care. For medicaid HMOs their contracts specify wait times to measure. They were able to look at targets vs. actual wait times. A couple things stood out – there is significant variability in wait times for psychiatry services, mental health day treatment, AODA services etc. For outpatient psychiatry at least one carrier had a minimum wait time that was the maximum required in their contract. For medication assisted treatment which requires specific training and certification they are really missing the mark on many ways. There is a 72 hour max and they saw 1 day to 2 weeks to get an appointment.

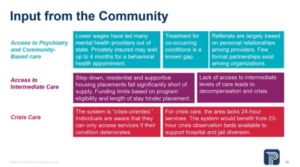

The stakeholders input broke down to three major themes. First was access to psychiatry and community based care is a challenge, particularly for people with co-occuring mental health and substance use. That is a known gap and there is a pretty high morbidity for that combination. They also heard in the focus groups with providers that the referrals are based professional to professional relationships. They know who they can reach out to and have good relationships and there is trust. This is less systematic than we see in other areas, normally they have agency to agency agreements.

For access to intermediate care, step-down residential facilities, supportive housing placements are all something that is lacking in Dane County, but also lacking across the country, they see this in every area that they work. That lack of access to intermediate care can lead to decompensation which can bring people into iris and back in to the inpatient system.

Largely because of the first two points, the stakeholders see the system as being crisis oriented. They know the individuals they work with have a perception that they can’t get care until their condition deteriorates and they are closer to crisis. Stakeholders thought there should be more options for crisis care including 23 hour observation beds and expanded access to overnight 24/7 care.

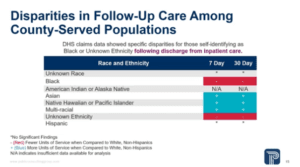

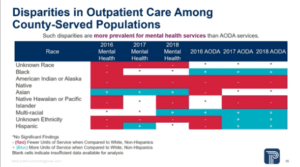

They know from other studies that there are disparities in access to mental health services in the African American community as well as access to insurance coverage for the Latinx community. Generally data on race and ethnicity is inconsistently reported. In the WHIO claims dataset they don’t designate race or ethnicity. The good thing is that they have very specific information from DHS so they could calculate some disparity outcomes. Follow up care is important because it reduces readmissions and decompensation into a crisis state after discharge from the hospital. What they saw was that people who self identified as black or African American were less likely to get the follow up care following discharge from the hospital.

They says similar disbarring for outpatient care and they were more prominent for mental health than AODA services. They saw better outcomes for AODA services for some of the populations.

They says similar disbarring for outpatient care and they were more prominent for mental health than AODA services. They saw better outcomes for AODA services for some of the populations.

When they spoke to the stakeholders about disparities in care they had three main trends. There is an overwhelming desire to have more support between the providers and the communities to have more cultural competency and to create a more welcoming environment for all involved. The upside is that there were more community based organisations that had developed prevention programs for their communities so they have more outreach and early intervention happening with some of the communities, particularly the Pride community and the African American community. And lastly people of color are more likely to be incarcerated than treated in Dane County, that is an overwhelming perception. And that will lead into the section on law enforcement.

A couple other findings were that residential and step down services were accessed more by people covered by DHS than other payers in the dataset. Crisis services were a small portion of the claims over all but they saw more individuals accessing crisis services but less often between 2017 and 2018. And access to psychiatric services presents an ongoing challenge. That is mirrored across the country, not just in Dane County.

Kacie Schlegel says across the country jails and prisons have been known as being the largest provider of mental health services. They were able to obtain data from the Dane County Jail from Wellpath who provides mental health services.

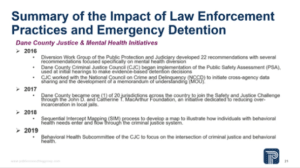

The data shows that almost half of the people in the Dane County Jail have received a previous mental health diagnosis. There are a number of initiatives under way to prevent using jail to treat mental health issues. Many of them are spearheaded by the Dane County Criminal Justice Council. Some things include introducing risk assessments, creating a data sharing MOU between all of the law enforcement agencies across the county, a sequential intercept mapping report which show the process of flow through the criminal justice system and creating a Behavioral Health Subcommittee that does a deep dive into the population and how they interact with law enforcement.

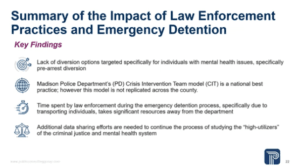

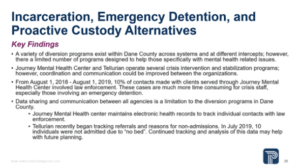

The key findings is that there are a lack of diversion oportunities targeted specifically for people in the criminal justice system with mental health disorder. Madison Police Department Crisis Intervention Team model is a national best practice, but it is not replicated across the county. Time spent during the emergency detention process takes a significant amount of resources away from the law enforcement department and additional data sharing efforts are needed to continue studying high utilisers of the criminal justice and mental health system.

The key findings is that there are a lack of diversion oportunities targeted specifically for people in the criminal justice system with mental health disorder. Madison Police Department Crisis Intervention Team model is a national best practice, but it is not replicated across the county. Time spent during the emergency detention process takes a significant amount of resources away from the law enforcement department and additional data sharing efforts are needed to continue studying high utilisers of the criminal justice and mental health system.

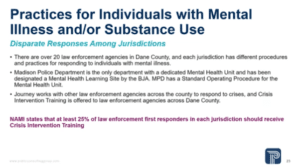

There is a disparate response among jurisdiction. The Madison Police Department is a national leader in their Crisis Response Team – they have 6 full time mental health officers and 3 in house Journey Crisis workers to help support them. Also, each of the law enforcement officers receives 100 hours of mental health and crisis response training. However in Dane County there are 20 unique law enforcement offices with unique responses to crisis and different staffing models. Journey does provide support to these law enforcement agencies, however not all are receiving the amount of support they need and stakeholders continue to report a lack of access to crisis and mental health services in the rural areas.

Data and information sharing is crucial to tracking and improving outcomes. The CJC (Criminal Justice Council) MOU includes law enforcement agencies but not behavioral health providers. Tracking and sharing the data is crucial in helping identify high utilisers in both systems to divert them from the criminal justice system and get them into adequate treatment services to address other underlying mental health issues.

It’s common to call law enforcement to deal with mental health crises within the community, however the current diversion options in the criminal justice system are not specifically centered on mental health. There is a full list of all the diversion programs in the report (Drug Court, Veterans Court, Deferred Prosecution) but none have a specific mental health focus. Additionally Journey has crisis units that are meant to help divert people into treatment but they have issues with capacity in meeting all the crisis and mental health needs in the community related to staffing, wages, filling their overnight positions to have full 24/7 crisis support. Their additional crisis and respite programs with Journey and Tellurian (like Resource Bridge) could expand diversion option but they have capacity issues related to the number of beds available, strict referral criteria. Many of them are step down for state hospitals instead of accepting referrals from community members. And just the ability to communicate with each other and plan for the full needs of the community related to capacity in mental health.

It’s common to call law enforcement to deal with mental health crises within the community, however the current diversion options in the criminal justice system are not specifically centered on mental health. There is a full list of all the diversion programs in the report (Drug Court, Veterans Court, Deferred Prosecution) but none have a specific mental health focus. Additionally Journey has crisis units that are meant to help divert people into treatment but they have issues with capacity in meeting all the crisis and mental health needs in the community related to staffing, wages, filling their overnight positions to have full 24/7 crisis support. Their additional crisis and respite programs with Journey and Tellurian (like Resource Bridge) could expand diversion option but they have capacity issues related to the number of beds available, strict referral criteria. Many of them are step down for state hospitals instead of accepting referrals from community members. And just the ability to communicate with each other and plan for the full needs of the community related to capacity in mental health.

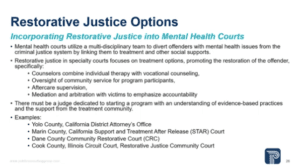

As part of the report they were supposed to look at Restorative Justice Options as it relates to mental health and law enforcement. One option that is popular across the country is the use of mental health courts – they are used to address treatment needs of the offenders without sacrificing the safety of the community. They are collaborative and take a multi-disciplinary approach to addressing services. That means they have partnerships with law enforcement agencies, the prosecutors office, probation, the public defender, judges, as well as behavioral health providers to provide wrap around services to individuals and truly address the underlying needs that have put them in to the criminal justice system. There are over 300 courts around the country and they are supported largely by mental health advocacy groups, not as a first line of diversion, but it targets frequent users in the criminal justice system. In evaluations of mental health courts, it shows they reduced recidivism, the overall cost on the system and increase access to mental health services.

As part of the report they were supposed to look at Restorative Justice Options as it relates to mental health and law enforcement. One option that is popular across the country is the use of mental health courts – they are used to address treatment needs of the offenders without sacrificing the safety of the community. They are collaborative and take a multi-disciplinary approach to addressing services. That means they have partnerships with law enforcement agencies, the prosecutors office, probation, the public defender, judges, as well as behavioral health providers to provide wrap around services to individuals and truly address the underlying needs that have put them in to the criminal justice system. There are over 300 courts around the country and they are supported largely by mental health advocacy groups, not as a first line of diversion, but it targets frequent users in the criminal justice system. In evaluations of mental health courts, it shows they reduced recidivism, the overall cost on the system and increase access to mental health services.

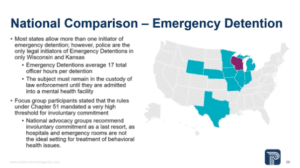

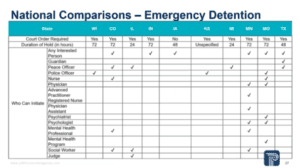

They did a comparison of WI and peer states on emergency detention laws. They compared the level of judicial oversight, who is legally allowed to initiate an emergency detention, the reasons for commitment etc.

They did a comparison of WI and peer states on emergency detention laws. They compared the level of judicial oversight, who is legally allowed to initiate an emergency detention, the reasons for commitment etc.

The key findings were that in only two states – Wisconsin and Kansas – law enforcement officers are the only legal initiators of emergency detention holds and that creates a burden for two reasons. The sheer amount of time to initiate the process – its 17 law enforcement Hours per detention and the reason it takes to long is because they must remain in law enforcement custody until they have been admitted to a health care facility. The law enforcement officer must be present during testing, assessments, labs and transporting a person to a facility. In 2018 there were 252 detentions in Dane County. The other reason is that studies show when law enforcement are the only ones to initial detention, that results in incidents of arrest. Best practice recommends that friends and family should also be allowed to initiate the detentions because they are better aware of the persons mental health needs and can best address them. Lastly they heard from statkeholders that there was a high threshold for involuntary commitment, which is not emergency detention – emergency detention is the first step that could lead to involuntary treatment. Involuntary treatment should be used as a last resort and only when there is a serious risk of harm. That is a good thing because hospitals and emergency rooms are not the ideal setting for mental health treatment.

Alecia Holmes is back to talk about Crisis Restoration Centers.

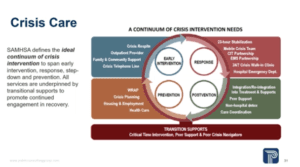

She says they will start with best practices for the continuum of care – one goal of crisis care is to mitigate the risk of future crises. They are not just looking at the services provided during a behavioral health crisis but also what is happening before and after to prevent additional crises in the future.

She says they will start with best practices for the continuum of care – one goal of crisis care is to mitigate the risk of future crises. They are not just looking at the services provided during a behavioral health crisis but also what is happening before and after to prevent additional crises in the future.

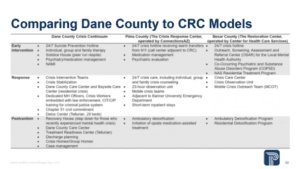

To help them understand the scope of services around the continuum in Dane County they compared the services to two well know crisis restoration models. One is in Pima County Arizona and the other is in San Antonio. She doesn’t go through them, but for Pima County it serves the entire county with a population of a little over 1M so double Dane County, they have a lower average income and 18% uninsured rate, which is more. For San Antonio, even tho they serve the whole county, the primary source of referrals is from the City of San Antonio and that is 1.5M residents, also slightly lower income and a 17% uninsured rate. Quite a bit different payer mix happening than in Dane.

To help them understand the scope of services around the continuum in Dane County they compared the services to two well know crisis restoration models. One is in Pima County Arizona and the other is in San Antonio. She doesn’t go through them, but for Pima County it serves the entire county with a population of a little over 1M so double Dane County, they have a lower average income and 18% uninsured rate, which is more. For San Antonio, even tho they serve the whole county, the primary source of referrals is from the City of San Antonio and that is 1.5M residents, also slightly lower income and a 17% uninsured rate. Quite a bit different payer mix happening than in Dane.

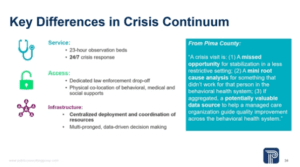

The differences is that both of the centers have 23 hour observation beds available and the other is that there is an expansive access to 24/7 crisis response systems. The Tucson CRC is well known for its dedicate law enforcement drop off, they have a separate sally port entrance for law enforcement and they are reporting an average turn around time of 10 minutes for law enforcement interaction before the person is taken into care. The other piece that is common to both of these is that there is physical co-location of more services including peer programs and care coordinators that are all in the general campus of these crisis restoration centers. The take home with both of these is the overarching organisation. What they see is that the success of both of the centers hinges on a high level of coordination with their provider partners and also the other payers in the communities, they focus on heavy data sharing and that is where they see the success in these models. Pima County, Dr. Balfour said it best in this quote “A crisis visit is 1) a missed opportunity for stabilisation in a less restrictive setting 2) a mini root cause analysis for something that didn’t work for a person in the current behavioural health system and 3) if aggregated, a potentially valuable data source to help a managed care organisation guide quality improvement across the behavioural health system.” It’s a very data oriented system that is looking at and trying to impact the entirety of behavioral health services in the area.

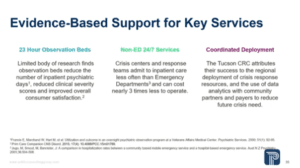

For the key differences they dug in to the research based evidence behind the practices. For 23 hour observation beds there is a limited but compelling body of evidence that suggests that 23 hour observation beds can reduce the number of inpatient psychiatric days for individuals admitted, they reduce the clinical severity scores for people in the programs and improve overall consumer satisfaction with the services provide. Fro 24/7 crisis services the point is that we are taking people out of the emergency department more often. That is important because emergency department staff have been shown to admit to in patient levels of care more frequently than from crisis teams. They are able to save money and keep people out of the in patient levels of care when it is not truly necessary for them. Lastly, the Tucson CRC attribute their success to end to end coordination of the crisis response system. From the payers to the responders to all of the transitional supports they are creating a data driven broad system of care that leads to successful outcomes.

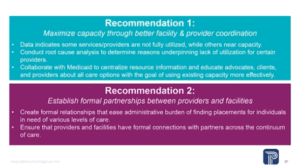

Rich Albertoni says that the recommendations are 7 areas of focus. The first is maximizing capacity. They found over-utilization with some providers and under-utilization with others and they weren’t using the resources as a system and the system wasn’t optimized. There were referrals to known providers and not much of an awareness of the broader capacity of the system.

The second part of optimatizing the system is greater formal partnerships between providers and facilities, usually in the form of MOU. Does an inpatient facility actually have a MOU with a step-down facility? That would be an example of formal relationships.

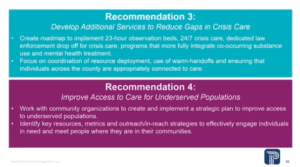

#3 is specific to gaps in the service array, specifically the 23 hour observation beds and expanding 24/7 crisis care, especially in rural areas. And increase services that integrate mental health and AODA.

#4 is the disparities based on demographics. They are recommending a plan to address those. They feel this should be structured with key resources, metrics, outreach strategies . . .to make sure all individuals in the county have equal access.

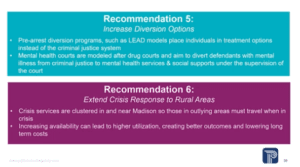

#5 is increasing diversion options, specifically with the LEAD model and the mental health court. Just that one statistic of the number of people in Dane County Jails that do have a mental health diagnosis and try to increase the diversion options.

#6 Extend crisis response in the rural areas. A lot of that is criminal justice focused where there is one state of care in the City of Madison that is associated with law enforcement and a different state of care outside of Madison with suburban and rural areas.

The last recommendation is the most ambitious longer term. Good mental health care is related to good physical health care, social services, and social determinants of health. This is to create an infrastructure to allow the different sectors to communicate and plan together so they have integrated care that is physical, behavioral, social service and that is going to take some time to build.

The last recommendation is the most ambitious longer term. Good mental health care is related to good physical health care, social services, and social determinants of health. This is to create an infrastructure to allow the different sectors to communicate and plan together so they have integrated care that is physical, behavioral, social service and that is going to take some time to build.

QUESTIONS

Sharon Corrigan asks about the Crisis Centers, you said we needed to expand their beds and she led a team to visit Pima, Supervisor Rusk joined the group and she says they said to expand, but didn’t recommend having a restoration center here, did you look at that vs. expanding the use of beds at Tellurian or other places? Or did you have more specific recommendations.

Kacie Schlegel says that at this time, with the landscape of the providers and the gap in coordination, they felt adding a brand new brick and mortar facility with a new provider on top of the other providers in the system wouldn’t be prudent at this time. Instead they propose a methodical expansion of the existing crisis services, really focusing on collecting more discrete data as they do the expansion and adding the particular types of services including the 23 hour observation beds and expanding mobile crisis for 24/7 care.

Corrigan says that is would be another provider to take individuals dropped off by law enforcement to achieve the 10 minute drop off in some way. Schlegel says there are a couple of ways to go about the 24 hour drop off. This was something that for Pima County CRC that was a separate entrance to an existing building to create the additional access for law enforcement. What they are envisioning is looking at the contracts you have with the crisis providers and their existing capacity as far as the existing brick and mortar infrastructure they are working with and seeing what small changes could be made to accommodate these services and fold them in over time.

Paul Rusk says he was struck with they have very little in there about the private sector. He believes if the private sector which covers 70-75% of the people in Dane County did a better job, we wouldn’t have so much of a problem in the public sector. We keep doing everything we possibly can to include the public sector, but the private sector where the majority of the population gets its health care he believes is not doing very well. Did they look at that at all.

Rich Albertoni says you see that in our first couple recommendations, which are optimizing the system you have, which is largely private sector providers. Recommendation 2 is an example of that where they want it to be more structured, they believe there is an opportunity for providers to not just think about their own enterprise but how they interface with the broader system and have MOUs with other providers and improve the way they function in the greater system. He says they tried to address it and they see it in some of the recommendations.

Rusk says its up to the public sector to reach out to the private sector and put this in place?

Kacie Schlegel says unfortunately typically that is the way it goes. What they see with the counties and jurisdictions that they have worked with in the other parts of the country, it is the public sector that initiates that contact with private payers and brining in folks who are operating in the commercial sector. One way to start the conversation, and they started it during their work, is better coordination with the Department of Insurance for the State of Wisconsin and understanding how they are regulating the payers that are coming through. All the payers on the commercial side are subject to the mental health parity and addiction equity act established in 2008, expanded in 2010 under the Affordable Care Act. That has specific requirements for network adequacy, making sure access to services is no more restricted for mental health than it is for medical and behavioral health. It has taken a really long time, its 2019 and just in the last few years they have been working with insurance departments to nail down the provisions of that act and how compliance works in the private sector. Its counties, government, who is reaching out to the private sector and saying you have to come to the table, we need to address this together and they have seen positive results – particularly in Delaware where they brought public and private sector together.

Carousel Bayrd asks about mental health court. A few years ago there was an effort to develop a mental health court and the conclusion by the judges was that they didn’t want the court. They wanted drug court and didn’t want a separate mental health court but they wanted each of the 17 judges to have the mental health tools because it was too engrained in too many different areas that it didn’t belong in one court. What kind of resources can they have to start the process again. Judges are a separate branch of government, how can we re-reflect or what are your thoughts on the conclusion that they drew.

Holmes says you need judge buy-in to have a mental health court and best practice is that there is one judge running the court, that is a key component. She would direct them to the BJA (Bureau of Justice Assistance), they have done numerous studies on the benefits of having a mental health court. She agrees that mental health issues don’t happen in a vacuum which goes to recommendation 7, but mental health courts have been very effective to have people access treatment and address underlying mental health needs and getting them out of the criminal justice system.

Albertoni says that the consistency in which people are treated, if there is a specialty it is easier for people to be consistently treated the same and their needs addressed than if you try to have the whole system try to accomplish it.

Holmes says that Journey was on board with exploring, and there has been a small amount of money set aside to study a mental health court again in Dane County.

Carousel says she knows there are pre-sentence and post-sentence and some like the CJC we already have. Do you have an opinion on ones that are more successful than others. They don’t think there have been studies on which are more effective but it is her personal opinion that you want to target – it should not be a first sign of diversion – you want to target people who are frequent users of the criminal justice system, that is when it is most effective post-diversion. Post arrest diversion option, you don’t want to throw people in a mental health court when they could be treated in the community and not mandated by the court to do so.

Heidi Wegleitner says they talked about the Madison Police Department and held them up as an example because of their CIT (Crisis Intervention Team), MPD officers have killed multiple people who are experiencing behavior health crises in the last few years, so she is concerned that even if they are trained and have mental health officers there is problem with implementation and she is wondering – the Madison Mayor has put out the idea of exploring mental health ambulances – non-law enforcement emergency response teams. She asks if they looked at a non-law enforcement crisis response team and did they actually look at how the Madison Police are responding on the ground to crisis or did you just look at the model they are trained in and supposed to be utilizing.

They say that they looked at mental health ambulances and that is what they want the Journey Mental Health Crisis Response team to be, they frequently go out and respond to crises without law enforcement. They have a crisis line and whenever possible that should absolutely be the way to go, if you have the resources and capacity to address a mental health crisis without the involvement of law enforcement then you want to address the crisis in the least restrictive setting possible – typically that is without law enforcement involvement. They looked at the model mostly, they did talk to stakeholders and crisis intervention training is a national model that focuses on de-escalation but they did not go into the field to observe, that was outside of their scope.

Yogesh Chawla asks about recommendation #3 to reduce gaps and they said one of the biggest gaps is the 23 hour observation beds and you didn’t recommend a new brick and mortar facility and he wants to know what organizations they would partner with to have those observation beds, what would those financial agreements took like and would they still be able to get the cost target to have it be 3 times less to operate and what safeguards can we put in so people having a mental health crises are not incarcerated, what best practices can we put in so people who are brought to the facilities don’t ultimately end up in jail.

They say a big part of the recommendation is the creation of the road map to create the service. They need to bring the providers to the table, open the contracts and have a frank conversation about where they might have capacity (physical and staffing) to support 23 hour observation beds or convert some of the facility. That may or may not be feasible under their current structure but the first step of that conversation to see what they have currently (physical space and staffing) and how they would need to augment the services to have 23 hour observation beds. To keep people out of the criminal justice system a key function is follow up after discharge, they talked about it after in patient, but its just as important after crisis. They want to make sure that especially for people with social and other medical issues that exacerbates the symptoms, that they have appropriate care coordination to keep them in recovery and in their community and out of law enforcement.

Chawla asks about the mental health beds in the jail that they are expanding, could they be used as a quasi crisis restoration center. They say that their personal preference is to keep people who don’t have criminality out of the jail system, depending upon the physical plant there may be an opportunity for law enforcement drop off but there is nothing in the research that would point them in that direction. This is about having a conversation with providers in the community and making the best decision for Dane County.

Sheila Stubbs says Dane County has done a lot to move equity in our county, but she notices that when they talked about blacks and whites you said it was a perception for blacks and she is interested in why she chose the word perception vs. real. We are the worst state for black families to be raised and in Dane County we have the most staggering numbers in this country, so she is concerned about the word “perception” vs. reality. Holmes says that typically they use the word perception when they talk about qualitative input they get from stakeholders. Its not that they don’t believe the stakeholders, the basis of most of their recommendations comes from what they tell us, but we typically use the word perception when talking about that data vs. quantitative data which was really lacking for us in this area. They didn’t have the claims data to double verify what they were being told by the stakeholders, but your point is very well taken.

Jamie Kuhn asks about collaboration and how they can follow up on public-private partnerships. This study shows that we are sometimes not able to get information from the public sector and she doesn’t know that working with OCI alone will be the solution to that collaboration. She also believes it goes both ways. Can you talk about how you encouraged or nudged some community private partners to work with public entities on it. She says that underlines how to move forward on these issues.

They say that Delaware was their specific experience. This was a broader collaboration that included behavioral health but was focused on broad health care issues across private and public sector. The crux of that collaboration came from the Delaware Health Care Authority. They were appointed by the Governor, the Secretary of HHS and various members of the state legislature to participate. They had a broad charge and authority to implement new recommendations to put forward new funding recommendations and brought a lot to the table from their individual experience. They had small business owners, the chamber of commerce, insurance regulators, payers, medicaid and folks from various sectors across their industries and it was a pretty small community, even this they are a state, its similar to Dane County. They made the most progress on public and private partnerships. When they look at data specifically there are three examples – Camden N.J. which has a cross sector social services, law enforcement, health care, behavioral health all pulling data into a single repository that they have a large community of individuals that review the data and come up with program recommendations to improve for the most vulnerable populations in their community. New York City has done something similar, she believes it is limited to the administrative data through the city, but its also education, housing, health care, behavioral health, law enforcement all working together and they have multiple MOUs backing up that system – its another data driven model. They are also currently working with San Diego County to put together a similar cross-sector data set with a cross-sector governance work group to start to look at the data more specifically and use data driven decision making to come up with more methodical program development and more targeted program development to pinpoint the outcomes they want to impact for their community.

ADJOURN