Do we really need more officers? Or do we need police officers to stick with policing activities and find resources for other needed services? Greg Gelembuik spells it out for us, with data!

if you only read three things, look at the crime rate going down, our police force growing out of proportion with other policing agencies and our population growth. Something is amiss! We need to really study this more deeply to determine how many police we need.

Dear Alders,

I’m writing with respect to proposed 2020 Operating Budget amendments that would increase the number of MPD officers.

1. I commonly hear two arguments for increasing the number of police officers. Upon examination, neither really makes sense.

a. One argument is that officers should be added to control crime.

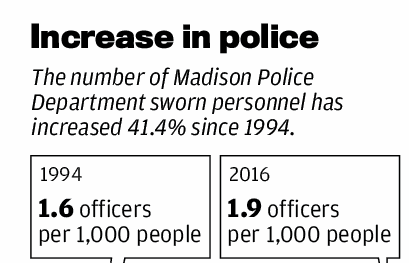

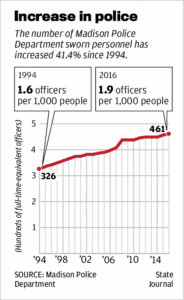

But it’s useful to understand what’s actually been happening with policing and crime in Madison. As a visual aid, here is a graph from the Wisconsin State Journal (spanning the years 1994 to 2016):

For comparison, here are numbers from the Uniform Crime Report for Madison population and number of crimes for 1995 (this data is not available for 1994) and 2016

City of Madison population

In 1995: 196,156

In 2016: 252,136

28.5% increase over this period.

Total number of crimes in Madison (property plus violent).

In 1995: 9,287

In 2016: 7,764

As you can see, growth in the number of Madison police officers is out of proportion to growth in the number of Madison residents and number of crimes (where the crime rate has gradually been declining over time). And this doesn’t even include growth in the number of UW and State Capitol police, who also provide policing in Madison. We’re continually expending a greater share of our limited resources on policing, at the expense of everything else.

And at the current level of policing in Madison, the addition of more officers will not significantly improve public safety or crime rates. As I noted previously, studies indicate that for a U.S. city with Madison’s characteristics, the benefit:cost ratio for adding officers (i.e., reduction in cost of crime to society) appears to be somewhere in the range from 0:1 (or possibly even negative) at worst to 1:1 at best. In contrast, as I’ve noted, many public health approaches to reducing crime have a benefit:cost ratio (i.e., reduction in cost of crime to society) that is far higher. For example, the Becoming A Man program (providing peer support and cognitive behavior therapy to at-risk youth) has a benefit:cost ratio somewhere in the range of 8:1 to 30:1 (and that is based on gold standard evidence from randomized controlled trials). So if you’re actually concerned about public safety and crime, allocating more resources to policing rather than to proven public health approaches does not appear to be a rational strategy.

On benefit:cost ratios and effects of policing on crime, I’ve provided more detailed information in response to a query from Alder Henak – I’ve linked a copy of my reply

here (and I appreciate Alder Henak’s inquiry).

b. The other argument I hear is that officers should be added to reduce patrol workload.

But if the goal is cost-effective reduction in patrol workload, it makes much more sense to allocate the funding to mobile crisis response units as in the

CAHOOTS program in Eugene and Springfield OR. I’ll note that implementation of such a program was one of the recommendation of the MPD Policy & Procedure Review Ad Hoc Committee (Recommendation #84). Such units can respond to most mental health calls, suicide prevention calls, intoxication calls, many dispute resolution calls, homelessness calls, etc. more effectively than police officers (who are less well trained for handling such calls than are mental health professionals) at lower expense on a per call basis. A survey by OIR found that MPD officers believed that they aren’t the most appropriate responders to many of the calls they are being dispatched to. And police officers frequently dislike being dispatched to mental health calls, since individuals with mental health issues often act erratically and can be difficult to deal with. In Eugene and Springfield OR, the CAHOOTS program handles most such calls, can better de-escalate such situations, and greatly reduces the number of such calls that patrol officers must respond to. Moreover, this is not some recent unproven approach – the CAHOOTS program has been operating very successfully for three decades, and similar programs exist elsewhere. Given the relative expense of adding patrol officers versus CAHOOTS-type responders, any given allocation of funds to the latter should generate a greater reduction in patrol workload than the equivalent expenditure on the former.

In Madison, once officers are added, those positions are locked in (will not be taken away and will need to be funded in perpetuity – we always rachet up, not down). That money should instead be saved for rational allocation to approaches that more effectively address these issues.

I will also add that I believe a point raised by Alder Furman has validity – in seeking to address MPD workload issues, finding means to incentivize officer retention appears to make more sense than increasing authorized strength.

2. Why has the number of MPD officers been rapidly growing over the last two decades? (see graph above)

If you look at the number of law enforcement officers across the U.S. over the last two decades, it has been relatively stable. From 2004 to 2018, the number of full-time law enforcement officers in the U.S. shifted from 675,734 to 686,665, which actually represents a decline in the officer to population ratio. Madison strongly defies that trend.

And the rising number of officers and the rising officer to population ratio in Madison isn’t being driven by crime rates, since crime rates in Madison have been gradually falling (the same pattern you see nationwide).

So why is police force size growing so rapidly in Madison when police officer numbers are not increasing across the U.S., and during a period when crime is falling in Madison? In 1994, Madison’s officer to population ratio (1.6 per 1000) was exactly what you’ll now find in an average U.S. city with Madison’s population and crime rate. What caused the number of officers in Madison to shoot upward since then, diverging from the generally stable pattern seen across the country?

Research on police force size and officer to population ratios does provide a pretty clear answer to this apparent paradox in Madison. White fright.

Many studies have examined the factors that drive police force size in U.S. cities, and

the evidence is now overwhelming that perceived racial and ethnic threat is one of the strongest factors, and this is independent of crime rates. As predominantly white cities diversity, as has been occurring with Madison, many white residents perceive a threat from growing communities of color. Given that perception of threat, they then demand increased policing, and politicians respond by increasing police force size. Moreover, research shows that this pattern is intensified, again independent of crime rates, when there is greater inequality between whites and communities of color. For example, as illustrated in “

The Persistent Significance of Racial and Economic Inequality on the Size of Municipal Police Forces in the United States, 1980–2010“:

in a large sample of U.S. cities between 1980 and 2010, we find that racial threat and economic inequality work both independently and jointly to produce substantial shifts in the size ofpolice forces after accounting for levels of crime as well as other important demographic and structural characteristics.

Note that such disparities in Madison and Dane County are particularly severe, as pointed out in the Race to Equity Report and subsequent analyses, exacerbating the perception, among whites, of racial threat. And in Madison, pressure for hiring more officers appears to be disproportionately coming from older white homeowners living in neighborhoods that are rapidly diversifying. In response to such political pressures, and despite the fact that objectively, crime rates have been declining, elected officials have continued to expand the authorized size of MPD, consistent with what has happened in other similarly diversifying cities across the U.S.

This pattern of police force size being driven by perceived racial and ethnic threat is not confined to cities in the U.S. For example, as noted in “Structural Determinants of Municipal Police Force Size in Large Cities across Canada: Assessing the applicability of ethnic threat theories in the Canadian context“:

Dozens of empirical studies on the size ofmunicipal police departments have been conducted in the United States over the last 20 years, and the vast majority of this scholarship has pointed to the strong role that the racial composition of a city plays….

Together, the results from our regression analyses point to a robust relationship between the size of metropolitan police departments across large Canadian cities and specific contextual factors, particularly the city’s ethnic composition and the level of poverty. These associations persist even after conventional accounts such as the crime rates, population, and budgetary constraints are accounted for. These findings are not only consistent with the vast majority of prior scholarship on police strength in the United States (e.g., Carmichael & Kent, 2014; Kent & Carmichael, 2014; Kent & Jacobs, 2005; Stucky, 2005) but they also offer strong support for the applicability of minority threat theory in Canada. Thus, despite rhetoric to the contrary, dominant group members in Canada appear to hold deep-seated prejudice and mistrust of ethnic minority groups and the consequences for minorities may be substantial, including greater criminal justice oversight of their communities.

Madison has one of the worst racial disparities in arrest rates in the nation (with black residents

arrested at more than ten times the rates of whites). At this point, half of MPD arrestees are black, and the proportion has been rising steadily, including over this last decade. Unfortunately, the current trend of expanding policing and the criminal justice system has long-term consequences that exacerbate the underlying stratification (a negative feedback loop). And the long term consequences are counterproductive to the intended goal of improving public safety.

A few examples of the research on longer-term effects of expansion of criminal justice approaches:

Using four waves of longitudinal survey data from a sample of predominantly black and Latino boys in ninth and tenth grades, we find that adolescent boys who are stopped by police report more frequent engagement in delinquent behavior 6, 12, and 18 months later, independent of prior delinquency, a finding that is consistent with labeling and life course theories. We also find that psychological distress partially mediates this relationship…. Police stops predict decrements in adolescents’ psychological well-being and may unintentionally increase their engagement in criminal behavior.

An increasing number of minority youth experience contact with the criminal justice system. But how does the expansion of police presence in poor urban communities affect educational outcomes?… Under Operation Impact, the New York Police Department (NYPD) saturated high-crime areas with additional police officers with the mission to engage in aggressive, order-maintenance policing. To estimate the effect of this policing program, we use administrative data from more than 250,000 adolescents age 9 to 15 and a difference-in-differences approach based on variation in the timing of police surges across neighborhoods. We find that exposure to police surges significantly reduced test scores for African American boys, consistent with their greater exposure to policing…. Aggressive policing can thus lower educational performance for some minority groups. These findings provide evidence that the consequences of policing extend into key domains of social life, with implications for the educational trajectories of minority youth and social inequality more broadly.

A new paper from University of Michigan economics professor Michael Mueller-Smith measures how much incapacitation reduced crime. He looked at court records from Harris County, Texas from 1980 to 2009. Mueller-Smith observed that in Harris County people charged with similar crimes received totally different sentences depending on the judge to whom they were randomly assigned. Mueller-Smith then tracked what happened to these prisoners. He estimated that each year in prison increases the odds that a prisoner would reoffend by 5.6% a quarter. Even people who went to prison for lesser crimes wound up committing more serious offenses subsequently, the more time they spent in prison. His conclusion: Any benefit from taking criminals out of the general population is more than off-set by the increase in crime from turning small offenders into career criminals….

Prison obliterates your earnings potential. Being a convicted felon disqualifies you from certain jobs, housing, or voting. Mueller-Smith estimates that each year in prison reduces the odds of post-release employment by 24% and increases the odds you’ll live on public assistance. Time in prison also lowers the odds you’ll get or stay married. Being in prison and out of the labor force degrades legitimate skills and exposes you to criminal skills and a criminal network. This makes crime a more attractive alternative upon release, even if you run a high risk of returning to prison.

So diversification leads almost invariably to increased perception of racial and ethnic threat and the belief among whites that they’ll be victimized by crime, which leads to political pressure for increased policing and expansion of criminal justice approaches, which leads to expansion of policing and jails (as has occurred in Madison), which leads to more police stops, citations, and arrests in communities of color, which leads in the long term to impaired educational outcomes, impaired earning potential, and criminogenic effects, which leads to entrenchment of communities of color in an underclass status.

Madison wishes to perceive itself as more progressive, tolerant, and astute in its approaches than other U.S. cities, but the actual patterns shown by the data, at least to this point, appear belie that perception – it appears that we’re no different than most other U.S. cities; responding to diversification by expanding policing. Elected officials would be wise to follow a path grounded in enlightened evidence-based practices, including the use of public health approaches to public safety, rather than further expansion of criminal justice approaches.

Sincerely,

Dr. Gregory Gelembiuk

people are just more dangerous now than they used to be