Madison, WI – Tonight the County’s Zoning and Land Regulation is going to be looking at if Dane County (including Madison) could do a project similar to what Hennepin County is doing – mapping structural racism in housing through deed restrictions. Check out what they found!

This is a project that people were talking about after the Dane County Housing Summit. I’m just catching up with it now, but its also on the agenda for the Zoning and Land Use Committee to talk about tonight. I thought some people might be interested in learning more about the project. More videos from the housing summit here.

VIDEO FROM HOUSING SUMMIT

The beginning of the presentation is cut off, but the video starts off giving an example of a covenants that they are mapping in Hennepin County, Minnesota. Here are the handouts from the presentation. Kirsten Delegard is the woman who is speaking from the Mapping Prejudice project.

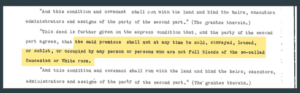

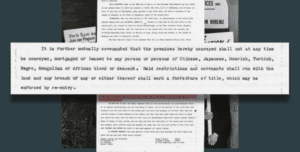

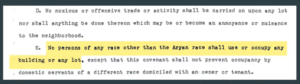

Even though this language is is offensive and shocking “no person of any race other than the Aryan race shall use or occupy any building or any lot.” That’s from 1946, so that’s after the Holocaust just to give you the context.

“no person of any race other than the Caucasian race shall use or occupy any building or any lot except that this covenant shall not prevent occupancy by domestic servants of a different race domiciled with an owner or tenant”

So what we’re doing is we’re leading community members in the work of taking this text and putting it on a map. So we we used computers to do some of the initial heavy lifting, combing through millions of property records to flag the documents that that seemed likely to have this kind of racist language. Then we recruited thousands of volunteers (close to 3,000 volunteers) who read a hundred and seventy thousand deeds on our online crowdsourcing platform and extracted the information that Kevin needed to to put them on a map. No one has ever created a comprehensive map of this kind in Minneapolis or in any other city. Here’s what we have documented so far so. (see video at 1:45) What you’re seeing here you’re seeing this time-lapse map of the spread of racial covenants through Hennepin County over time. Each one of these blue dots denotes individual property that was reserved exclusively for the use of white people. On this map as it cycles to the end you can see the date in the in the upper right hand corner, there’s there’s already a lot of blue on this map, but it doesn’t show all the parcels. We’ve actually just finished the work of volunteer transcription so there are many more parcels that we haven’t had a chance to put on this map yet. By the time that we’re finished, probably around the end of the year sometime, you’ll see about 30,000 covenants on this on this time-lapse map. The text that you have and the text that I read shows you how incredibly racist these deeds were. You can’t mistake the the purpose.

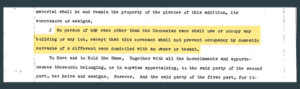

This map shows you how widespread. But in order to really understand why this is significant you have to understand how powerful these instruments were. To fully grasp this you have to understand how they were enforced. These covenants were contracts, so that means that they were enforced by the full power of the American judicial system. Covenants ran with the land meaning that they could be enforced through the court system decades after they were embedded into deeds. And anyone who dared to breach a covenant, even decades after was put into place, even after the property had changed hands multiple times, risked ending up in court. Anyone who sold land that had this kind of covenant on it, to a person who was not not white, risked losing all the property, all the equity that they had accumulated in the property. This was a violation of the original property contract, it could trigger a process that would put the property back in the hands of the person who put the covenant in place in the first place, even if that person were no longer alive it would just revert to their heirs.

So here’s some of the painful truth about covenants. Sometimes people stop me at this point in the presentation and they say tell me about the people who protested, tell me about the people who resisted. Here’s the painful part, is that most white people (and we have a lot of survey data to show this supported this) thought it was necessary. They did not believe that these restrictions, these covenants, violated either our social compact or our Constitution. There were those white people who did question and condemn these practices but the stakes were really high if they if they went against these. Few people were willing to put the entire life savings of their families on on the line. When you see so many people I think people questioned well how effective that would be. But for black people was a different story, black people put everything on the line to challenge these practices. They bought houses with covenants, they moved into white neighborhoods, they asserted the right to live where they wanted.

For instance, in 1931 the Lee family moved into a tiny white bungalow in South Minneapolis and they quickly found themselves under siege by white neighbors. The family actually had to retreat to the basement for safety because so many people were shooting through the windows and trying to kill the family. The only way that they were able to remain in the house and that the room the house was not burned down was Arthur Lee, the husband in the family was able to call on two groups of people. One was a World War I veteran so he could he called on his army buddies and then he called on his colleagues at the post office, fellow union members. Those two groups formed an armed perimeter around the house. Despite this the mob only grew. It stayed in place through most of the summer of 1931. One person described it this way, 6000 white people waiting to see that house burned.

So this morning when I heard the talk about toxic stress in childhood I was thinking about Arthur and Edith Lee’s daughter Mary Lee who was five years old when her family was attacked. Mary Lee’s experience was not unique, talk about toxic stress.

As these racial boundaries hardened in American cities during the first half of the 20th century this threat of white violence was ever-present. So covenants were enforced by both the law of the courts and the law of the streets. African-americans resisted in both arenas. The Lees weren’t alone. Folks moved into neighborhoods, they asserted their right to live where they wanted and they went to court. The N.A.A.C.P. brought a series of court challenges that ended up at the United States Supreme Court in 1948, that was the year that body declared covenants to be unenforceable. Unfortunately that wasn’t enough to stop this practice. A few years later elected officials had to make covenants illegal through legislative action. The Minnesota State Legislature did this in 1953 by banning new covenants. It didn’t outlaw covenants that were already in place, that happened in 1962 when the Minnesota State Legislature passed one of the first state fair housing acts in in the country. The federal government didn’t follow suit until until 1968 of course when it passed the Fair Housing Act.

A lot of times when people have talked about covenants, when they’ve told the story of covenants or they’ve told this history the story has stopped there. People have said it’s a story of triumph. We had this practice that was terrible, our institutions corrected for it, we made it right. Unfortunately that’s not true. We would like to believe collectively that these bad deeds are in the past, it’s just not true. We’re living with the legacies of these covenants. I liken it to if you have a stab wound, if you pull the knife out that wound doesn’t automatically heal. You have to do some work to to to heal the wound, the wounds inflicted by white supremacy.

To understand really how deep these wounds are we have to go back to 1910 when the first covenant was put into place to understand how these instruments really changed Minneapolis. From Minneapolis you can extrapolate out, Minneapolis is unusual in some ways but it’s largely the same.

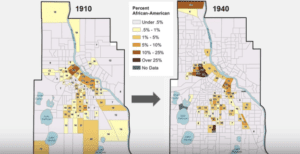

When the first covenant was introduced in 1910 there were only about 2700 African-americans in Minneapolis and this is a demographic a map that shows census demographic data from that year. The darker colored polygons indicate the the presence of African-american residents. What it shows the fact that you have different colored polygons across the city it shows that black people were spread pretty evenly across the city. The city was just not particularly segregated in this year, the city that had the highest percentage of black residents was near north, it’s that polygon that says 256 up there. But even that area, even that little concentrated neighborhood, only had 15 percent of its residents who are African-american. And you have you have African-americans living down in the southern part of the city, you can see around the lakes. I think this kind of geography, even if you might not be familiar with Minneapolis, I think you can take what you know about Madison to know that you know lakefront property is usually I’m pretty desirable.

This could have continued, the city could have allowed the African American community to stay and to continue to spread out in the city as it grew, but Minneapolis made a very different choice. When I say “the city” it’s shorthand for a bunch of different groups – it’s business leaders, city planners, neighborhood groups, bankers, government appraisers. They decided collectively, white people decided collectively, that it was important to impose what they believe to be a superior modern order on the urban landscape. They chose racial segregation.

At the cutting edge of this change was the real estate industry which was just coming into its own in these in these years. In 1913 local realtors adopted the ethics manual that had been published by the National Association of Real Estate Boards that declared in the ethics manual that it was unethical for a real estate agent to introduce into a neighborhood “members of any race or nationality whose presence will clearly be detrimental to property values.” So today we call this real estate steering. This was going on, but at the same time developers were experimenting with these racial covenants. In the decades that followed these legal instruments reshaped cities across America. Here’s what that looked like (see video 11:55) in Minneapolis by mid-century, from 1940 census data the demographic pattern looks radically different. You can see compare the two maps down in the southern part of the city, those people who were there they’re all gone. There’s no one living along the shores of Lake Harriet or Lake Nokomis and for the first time in the city’s history, multiple census districts are predominantly black.

So by 1940 after covenants had been in place for about 30 years. African-american residents of Minneapolis had been concentrated into a couple of small neighborhoods. Here’s a key point about this this has often been told as part of the story of the great migration, the great movement of people that brought people from the rural South to the urban north. But Minneapolis wasn’t an endpoint for the great migration in these years. That didn’t happen until much later in Minneapolis, in the 1950s. So in 1910 only about 1% of the city is African-american by 1950 it’s still only about 1.5 percent. In other words in these two maps it’s the same people but they have been relocated, they’ve been reshuffled out of the integrated space into highly segregated space. This is happening everywhere. African-americans in the words of the poet Langston Hughes were “hemmed in.” That’s the title of a 1949 poem he wrote about Chicago, where he said “they’ve got covenants restricting me, hemmed in on the south side, can’t breathe free” And in many cases in the neighborhoods where African-americans were restricted to, that was literally the case “can’t breathe free”

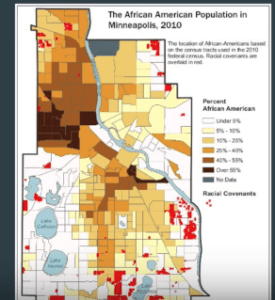

Once these demographic patterns got established they remained firmly entrenched. What this map shows – the red is is covenants that we’ve identified and they’re overlaid on a more contemporary census data from 2010. What it shows is that covenants are clustered on the sections of the city that are white today, a concentration of white people. No one has ever questioned this because these white neighborhoods are not seen as problematic. Instead all the attention, all the policy effort, has been directed at black neighborhoods that have been seen as inherently pathological in some way. The policy solutions that have been proposed and enacted, unfortunately, have been the opposite of effective. There’s there’s one scholar who who’s summed it up basically this way “whatever the problem is in the American city, the answer is to move the black people.”

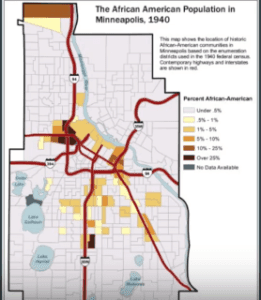

One way this was done was through freeway construction. In the 1950s freeways were regarded as critical to the growth of these new white suburbs. We have the data to show that these white suburbs were not white just by accident, they were white because they were covered with racial covenants. What freeways did is they allowed people to come from those suburbs to get to their jobs downtown. They were seen as having another benefit too, which was as engines of urban renewal. Their construction was used to clear neighborhoods that planners regarded as blighted. This map shows our contemporary freeway infrastructure in Minneapolis imposed on that earlier demographic date map from 1940. It shows what neighborhoods were regarded as blighted, the neighborhoods where people of color lived. This is not a new story, freeways displaced millions of people and destroyed hundreds of neighborhoods across the country that were inhabited by people of color.

Our team has thought a lot about covenants and why they’re important and why we’re spending so much time thinking about them. Here’s one of the things that we’ve concluded, that these restrictions were not intended as just a segregation mechanism. The ultimate goal of covenants was actually to keep people of color out of the city altogether. They came in the history of Minneapolis at a time when the black population was just tiny. The ultimate goal was to keep it that way and maybe even make it smaller.

When covenants were introduced in the early 20th century they they fit into already established practices around race and land tenure in Minnesota. Minnesota Michuche only became a state after native people were forced to cede their land to the federal government in the in the 1850s. The land that became Minneapolis was the historic home of the Dakota who were exiled from Minnesota after their defeat in the US-Dakota war of 1862. So Dakota people before they were deported from the state they were imprisoned in this internment camp at Fort Snelling.

The state put a bounty system in place which paid settlers for for Indian scalps and that was that was the system that was put in place to keep these native Minnesotans from returning home. This was around the same time that the state seal was adopted and it in the the picture the image tells the story of what people understood to be progress. It shows a Native American riding into the West, just disappearing into the Wild West as a farmer tills the ground in the foreground. So Minneapolis became a city soon after this. Settlers who were drawn to this to the city, they came from initially from New England and from Europe and they embraced this idea the story of of whiteness. So covenants were just one chapter in this larger narrative of white settlement. They were a new tool for realizing a long-standing vision.

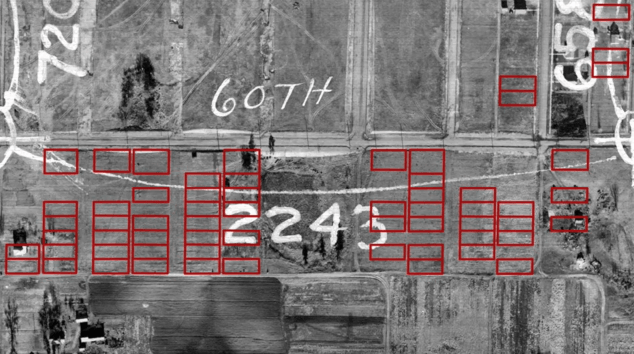

Developers soon realized that these these tools were most powerful if they were put into place just as neighborhoods were being platted. Here is a aerial photograph of south Minneapolis that was taken in 1938 you can see there was not much there, but these red polygons show the racial covenants that were already in place. When this picture was taken covenants were being embedded on the land before any other development takes place, before houses, before sewers, even before streets, the first things that developers are thinking about is race. This practice ensured that as American cities like Minneapolis developed that all the new development was reserved for white people.

I talked about the Lee family earlier, when an angry mob threatened to murder this family, when they killed the family dog, their plight elicited little compassion from their neighbors. It has been said “when you hurt a man’s pocketbook that is something that’s never forgotten. They talked about justice for the Negro, how about a little justice for the white man who has put his life savings into a home/” The writer he called for a systemic remedy he said, “You know if there was an any legal way of keeping a Negro out of a white district and ruining the value of everybody’s property for miles around, this would have never happened.” So the legal remedy was covenants. It seemed like the the common sensical solution for these people.

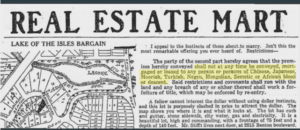

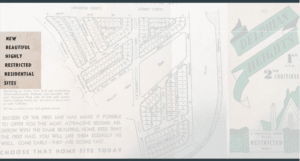

Developers soon caught on to this. They learned that these kinds of restrictions were powerful selling points. They used them as marketing tools. They printed them right into promotional material. This is a newspaper advertisement from 1919 that included the full-text of the covenant “shall not at any time be conveyed mortgaged or leased any person or persons of Chinese, Japanese, Moorish, Turkish, Negro, Mongolian, Semitic or African blood or descent.” So covenants they promised would safeguard people’s investments in their homes. In this promotional flyer for the Delphine edition new lots were touted as both beautiful and highly restricted.

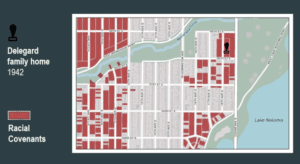

So for me this history is highly personal. I talked in the beginning about how when I embarked on this project it was out of this desire to merge the the personal and the professional. I didn’t quite understand how that would happen. At the same time that the city was pushing out newcomers, who were not white or perceived as not white, it was welcoming people like my grandparents. My grandparents were both from immigrant families with roots in Sweden. They started out their adult lives with no money and little formal education. Two of them had been orphaned at very young ages. None of them made it past the eighth grade. They worked in a whole variety of jobs all over the the region. My grandfather spent his early years on on a farm here in Wisconsin and he hired out as a as a farmhand, he then tried his hand in lumber camps, he tried homesteading in Montana. My grandmother worked as a domestic servant. My other grandfather worked as a carpenter. They tried their luck in all these little little towns in the 20s and 30s and then they decided to go to the big city in search of opportunity. It’s the classic immigrant story. During the Great Depression they they succeeded, they actually built businesses, they married they were able to save their money. In 1942 both sets of my grandparents bought houses. My grandfather actually hired a professional filmmaker to record the moment when he acquired property. It’s on youtube if you want to watch all hour and a half of it. It shows what a huge deal this was for my family.

It shows all these people coming he invited, everyone he had he had ever known and they were dressed in their finest clothes. They pulled up they were dressed in suits and dresses they walked around the house. The little guy in the front here is my dad.

Thanks to our map, I now know that this house had a racial covenant on it. The black icon up there in the upper right-hand corner. It’s on a block that’s blanketed by racial covenants. My maternal grandparents lived nearby and it was a same story with with their house. So although my grandparents were were new arrivals, they were regarded as white and that meant that they could build their lives in a place that was off-limits to other many other Minn with similar incomes and education.

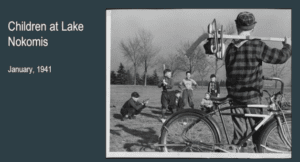

So I grew up hearing stories about this this neighborhood it’s near Lake Nokomis in Minneapolis. My parents described it they would tell these stories about how their moms pushed them out the door first thing in the morning and wouldn’t let them be inside. They spent all day at the parks at the lake swimming, skating in the winter, going to Minnehaha Creek. The neighborhood had really solid schools and both of my parents went to college even though their parents didn’t make it to eighth grade. My my mother went to graduate school. All this was only for white people. I’ve talked to my parents a lot about this now and they say that they never questioned why their neighbors were all Swedish, Norwegian and German. This overwhelming whiteness just seemed very natural to them. My grandparents bought their houses just as the United States was about to see the largest expansion of the middle class in its history. Much of this prosperity of course all of you know this rested on home ownership which had been deliberately supported by new federal programs in the 1930s, but these new programs of course they provided mortgage insurance and made cheap mortgages available to all kinds of people. They also introduced redlining. They were created to benefit people like my grandparents, and like the GI Bill they excluded people who were not white. So two generations later I am still benefiting from the fact that my grandparents were encouraged to buy houses in a part of the city where property values climbed for most of the 20th century. When my paternal grandfather died my family decided to sell his house and they split the profits of the sale amongst all the grandchildren, including me. I was able to use my portion to put a down payment on a house and another part of South Minneapolis that I could have never afforded without that help. I was looking basically to replicate my parents childhood for my kids. I wanted easy access to the Chain of Lakes, solid schools and though I was very very fortunate I am not unique in this story. I’m betting that all of you are familiar with the research that shows that 75% of first-time homebuyers get some kind of help from their family to manage the purchase of a house. We’re all doing the same thing, we’re leveraging the economic security of earlier generations to secure the future of our children. And my children have definitely reaped the benefits of that. I do want my kids to know and we talk about it all the time, that we carry our history with us, that none of us stand unencumbered in this moment. I want them to know that they live where they do today because of the opportunities afforded my grandparents. I want them to know that those avenues were closed to people who were not like that, covenants combined with redlining, the federal policy that deemed areas where African American people could live as too hazardous for conventional loans. These things work together to depress homeownership rates for African Americans. Today in the Twin Cities we have the highest gap between African American black and white homeownership rates for any major metropolitan area in the country. 75% of white families owned their homes and only 23% of African American families can make the same claim.

So mapping prejudice is designed to help people see structural racism. Most Americans have been taught to think that racism is a matter of personal bias that it’s the sentiments expressed by people like these protesters. We’re working to reframe this understanding, we want people to see that racist ideology has been embedded into the community. The founding documents of our community institutions over decades, that it’s created this map of privilege and dispossession where your destiny is determined by your zip code.

That its structures rather than individual bias or individual pathologies that have created and compounded the disparities that are so pronounced. This map that were making together with community members gives lie to a central myth about our community that we’ve been taught collectively that Minnesota and the north more broadly never had any kind of formal segregation. This history helps us to to understand why it seems to be the same group of people who are vulnerable to housing precarity/insecurity. The system was built to keep black and brown people from owning property. It was designed to keep them out of places that were perceived to be more desirable and the time has come to make amends for this.

What are we going to do next? What do we do with this? We are building with this work. We’re building a constituency for structural change, we’re inviting community members to help us document this deliberate campaign to create an all-white city. People who participate in this work experience a powerful challenge. These deeds are very clear about their intention and our volunteers are not just reading old documents, they are making a pledge to remember. They’re there making a pledge to make a difference going forward. I can tell you that thousands and thousands of people have come to our presentations, they volunteered for our project, they’ve wanted to engage with this history.

I believe that this is the first step for a long-term sustainable change, that injustice is rooted in amnesia but remembering is just a first step towards justice, we also have to see that this history demands reparations. Today you’ve heard about a litany of ideas that are designed to increase access to safe and affordable housing. So we need to do all of those things, we need to support both direct service and policy reforms. This is the first step, but we also need to extend this work by seeing it all through the lens of racial equity. Thanks to this history that I’ve been talking about today, this work cannot be erased neutral. This history explains, it begs the question how does this change our collective priorities? How do we change the way we support communities? So reparations, reparative work demand money but we also have to acknowledge that it’s going to involve cultural and moral capital. Reparations in the words of Ta-Nehisi Coates is “the full acceptance of our collective biography and its consequences” He writes that “it’s more than a recompense for past injustices, more than a hand off, a payoff, hush money or reluctant bribe. Reparations, in the words of Coates, “is a national reckoning that would lead to spiritual renewal.” So it’s my goal with this work to be part of that spiritual renewal and I know that all of you are also part of it as well so thank you.