This also wasn’t originally on the agenda and came out late yesterday. (4:11 p.m.)The police department was requested to file a report on:

- a history of the Department’s tear gas usage from 1990 up to and including August 1, 2020, that includes analyses of usage by year;

- incident type, including, but not limited to, crowd control, special operations, and smaller scale uses; estimated number of persons impacted; amount of tear gas used;

- justifications and efficacies of its usage compared to available alternatives; other pertinent information, and summaries thereof;

- MPD or non-MPD de-escalation alternatives to the use of tear gas, and that alternatives include, but not be limited to, response options from other agencies, organizations, health care entities, and suggested recommendations by the Quattrone Center’s analysis of the MPD’s May 30-June 1, 2020 response; and

POLICE REPORT HIGH LIGHTS

You can read the full propaganda here. I distilled the report below:

- a history of the Department’s tear gas usage from 1990 up to and including August 1, 2020, that includes analyses of usage by year;

- incident type, including, but not limited to, crowd control, special operations, and smaller scale uses; estimated number of persons impacted; amount of tear gas used;

2002

1 use for (1) barricaded subject – Mutual Aid request in Monona (Suicide attempt)

1 crowd control use – “A large crowd on State Street (Halloween weekend) became violent. Projectiles were thrown at officers and multiple fires were set. CS was used to disperse the crowd (four hand-thrown CS canisters).”

2003

2 uses for barricaded suspects – 1 person each

2004 – 2008

No usage

2009

1 use for a barricaded suspect – deployed in a cave, but the suspect wasn’t in the cave (suspect took their own life)

2010-2011

No usage

2012

1 use for a barricaded suspect – 2 people impacted

2013

2 uses for a barricaded suspect – 1 person impacted in each incident

2014 – 2015

No usage

2016

1 use – suspect found unresponsive from drug overdose – 1 person impacted

2017 – 2018

No usage

2019

1 barricaded suspect – not in residence, found in trunk of car – 17 canisters used – 1 person impacted – they don’t say how many people impacted, but easily 100s.

2020

3 days of using tear gas. 53 hand thrown canisters and 9 projectiles shot into the crowd.

During a three-day period in late May/early June Madison experienced significant civil unrest. This resulted in violence, extensive property damage, looting, and arson. More than 100 businesses or government buildings were damaged or looted; multiple MPD squads were damaged or destroyed; multiple fires were set; and the MPD rescue vehicle was struck by gunfire. Rocks, bottles, signs, and other projectiles were thrown at officers during the unrest (resulting in injuries to twenty-one officers). Law enforcement agencies from across the State were required to assist, as was the Wisconsin National Guard. Officers utilized CS (fifty-three hand-thrown CS canisters and nine 40mm CS projectiles) to address this behavior.

MPD has enlisted the Quattrone Center for the Fair Administration of Justice (affiliated with the University of Pennsylvania Law School) to conduct a sentinel event review of the 2020 unrest in Madison. This work is well underway, and MPD has been fully involved in the process. I anticipate their work to be completed sometime in early 2021.

- justifications and efficacies of its usage compared to available alternatives; other pertinent information, and summaries thereof;

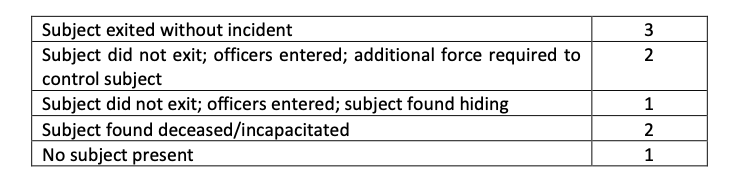

They state “The broad categories of CS deployment (tactical operations and crowd control) are quite different, and any meaningful assessment of CS use and potential alternatives must be focused on the deployment context.” However, they do not address it in the context of the incidents above. They do address the results of in the incidents with individuals:

- MPD or non-MPD de-escalation alternatives to the use of tear gas, and that alternatives include, but not be limited to, response options from other agencies, organizations, health care entities, and suggested recommendations by the Quattrone Center’s analysis of the MPD’s May 30-June 1, 2020 response; and

De-escalation for individuals:

De-escalation refers to a variety of tactics that officers can use in an attempt to secure voluntary compliance and reduce the need for the application of force during an encounter. MPD policy states that officers should utilize de-escalation techniques any time it is safe and feasible under the circumstances. De-escalation generally requires two things: time and the ability to communicate. It is most relevant when engaging an individual suffering from mental illness or under the influence of alcohol/drugs, rather than simply a noncompliant criminal suspect. Typical de-escalation techniques include distance, cover, concealment, and communication/persuasion.

This is what they state the alternatives are for individuals:

There are, unfortunately, very few options – other than chemical agents – available to force a barricaded subject from a dwelling. Examples include:

Illumination: directing lights at the windows of a dwelling occupied by a barricaded subject is a routine aspect of a tactical response. It might make it slightly less comfortable to remain in the residence but is unlikely to be successful in forcing someone to exit.

Cutting power: power can sometimes be cut to the dwelling where a barricaded subject is located. The intent is to make it less comfortable for the individual to remain inside by impacting temperature (depending on the time of year) and removing activities for the individual (watching television, etc.). Cutting power requires assistance from the applicable utility, and is typically only feasible for a single-family dwelling. It typically requires an approach to the dwelling (which creates risks), and has no impact on mobile devices.

Noise: Protracted loud noise/music can be used in an effort to force a barricaded subject (or subjects) to exit. Extremely high volume would be required to reach someone in a dwelling, and the adverse impact on surrounding residences is obvious. This is not a technique used by MPD.

Window/door breaching: Forcing a door or window open – but not immediately entering – is another option to encourage a barricaded subject to exit. Occasionally this will result in voluntary compliance, though it exposes officers to risk and generally is not effective with an uncooperative subject.

If entry is required, officers will utilize tools and techniques (robotics, for example) to minimize risk and increase the likelihood of a positive outcome.

De-escalation for crowd control:

Not addressed

Alternatives for crowd control:

Physical force: Lines or groups of officers can approach and physical engage members of the crowd to force them from the area. This requires a large number of officers, creates a greater risk of injury, and is more likely to result in additional escalation/confrontation.

Batons: Lines or groups of officers approach a crowd and use batons to force crowd members from the area. This also creates an increased risk of injury and additional escalation/confrontation. MPD primarily views officer lines with batons as a static, defensive technique to deny access to a particular area (and avoids doing so whenever possible).

Impact projectiles: In the crowd control context, MPD SOP only allows the use of impact projectiles to address an imminent risk to officers or others. And while MPD SOP does not allow it, impact projectiles could conceivably be used to move or disperse a crowd. Doing so, however, would create elevated risks of injury. There are a wide variety of impact projectile systems sold by manufacturers. MPD has chosen not to acquire or deploy most of these systems, based on accuracy, injury potential, or other issues.

Noise: Devices are available that can project loud audio towards a crowd or individual. The sound can be verbal commands/directions, or an “alert.” The “alert” sound is uncomfortable, and can be used as a mechanism to disperse crowds. Some have claimed that these devices can cause injury or hearing loss, and MPD has not utilized the “alert” option.

Water: While generally not used in the United States, some nations continue to use water cannon to disperse crowds. Use can create a potential for injury, and public perception associated with historical use in the U.S. make it an undesirable option.

Mounted Officers: Police horses can be used to physically move a crowd if needed. Typically this is more appropriate for nonviolent but noncompliant crowds, rather than under circumstances where an unlawful assembly has been declared (due to the risk to the horses from projectiles, fires, etc.).

Bicycles: Some agencies deploy officers with bicycles to create a static line/barrier, or to move a crowd. As with Mounted Patrol, this technique is most appropriate for nonviolent crowds. Using bicycles in this manner requires close proximity between officers and the crowd, and creates similar potential for additional confrontation or escalation as some other techniques (batons; physical force).

WHAT HAPPENS NEXT?

Unknown. Either an alder or two or three or more will use the info to introduce an ordinance or directive to the police department, or they won’t. Maybe it will get referred to the Public Safety Review Board (PSRC) for consideration. Also, the PSRC was told they would be the referral agency for city policies and Civilian Oversight Board would deal with internal police policies and complaints, but I understand that the ordinance may be referred to the Civilian Oversight Board as well. This raises an interesting question about when policies get referred to the new Civilian Oversight Board and when they get referred to PSRC. When the ordinance creating the Civilian Oversight Board was passed/recommended by the PSRC, we were distinctly told that the council would not refer policy items to the Civilian Oversight Board. I guess we’ll see.